Who was William Pondexter?

From Bondage to Celebrating a new life in Watertown

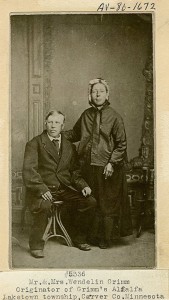

Juneteenth National Independence Day. It is a federal holiday in the United States, commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. Today’s story follows up on the mysteries surrounding William Pondexter and how a small community embraced a former enslaved person and ensured he was buried as one of their own.

Last year the Carver County Historical Society, the city of Watertown, the Watertown Area Historical Society, the Watertown City Cemetery and the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery received a joint Heritage grant to hire a professional researcher to attempt to locate some of the answers to the questions people have asked about William Pondexter’s tombstone, located at the Watertown city cemetery. While we did not learn as much as we had hoped, we did learn enough to answer some questions people have asked after viewing the tombstone.

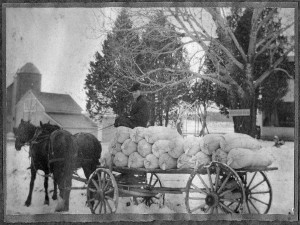

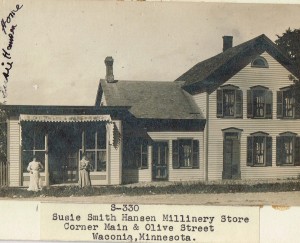

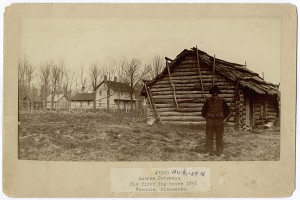

On September 28, 1911, William A. Pondexter died suddenly at the L. C. St. John Livery Barn, located at 109 Lewis Avenue North, Watertown. The Coroner’s Inquest and his death certificate state that he died of a rupture of coronary arteries, was married, and “about” 54 years old. His tombstone lists him as 51. His death certificate noted that he worked as a laborer. The document lists him as being born in the “south (slave).” No date of birth was given, nor were the names of his parents or next of kin. So began a journey to learn more about Mr. Pondexter and find answers to many of the questions people have been asked about Mr. Pondexter, including the most asked question, “Why is the word Negro is on his tombstone.”

To understand why and where Pondexter came from is a lesson in American history, following Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1963. At the time the document was signed, Pondexter was 6.

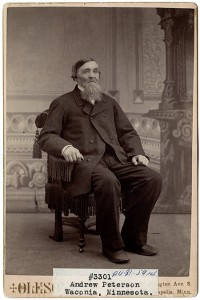

William Pondexter was an employee of the St. John Livery Barn. Newspaper accounts from several papers briefly noted his death. The Lester Prairie News stated that “The people of Watertown lost their bootblack and ham sandwich man one day last week. It’s certainly too bad.” (10/5/1911) As a 7 ½ year old, Gladys St. John remembered, via her journal, stopping by on her way home from school, she and many other people stopped to view Pondexter in his black casket. In this same journal, she wrote, “He was a very nice man.”

Not being a resident of Carver County, it and the city of Watertown chose to pay for the costs associated with his burial in the City Cemetery. This is pertinent as there was a potter’s field nearby where the destitute were buried. At the time, the plot was at the edge of the cemetery, but now it is nestled alongside a small creek and within 20 feet of the St. John family plot and Civil War veterans. The headstone itself presents several questions about burial practices and community relationships. The prominent racial designation, the style of the stone, and the level of weathering suggest the marker was placed by someone other than family members, likely sometime after the burial. This aligns with what was learned about Mr. Pondexter’s death- no family members were involved in any arrangements, and all expenses were handled by county and city officials. The prominent display of “NEGRO” on the headstone is particularly significant in understanding who likely placed the marker. During this period, racial designations on headstones were largely confined to markers placed by white institutions or authorities for African Americans – they do not typically appear on stones selected by African American families. Given that no family members appear in any death-related records, it is unlikely the marker was placed by Mr. Pondexter’s family, though we cannot determine who specifically was responsible for its placement. (Who Was William Pondexter? Anders Genealogical, 2024)

We do not know how or why Pondexter arrived in Watertown. There wasn’t anyone with the last name of Pondexter listed anywhere in the State of Minnesota in the 1870 and 1880 census records. This narrowed down his arrival time to between 1881 and 1911. He was not listed on the 1910 census in or around Watertown, which could mean he arrived after 1910 or that he was not counted in the census. Several Pondexters were found in MN in 1910, but each was ruled out except for four. One in particular stands out. The name William Pondexter was found in the Twin Cities 1910 directory by local researchers with an address of 1829 Minnehaha Ave. Unfortunately, grant funds had run out, making further research at this time impossible.

Today, take a moment to imagine yourself as Mr. Pondexter. He was born into slavery. Think about your move from bondage to celebrating freedom and a new life in Watertown. How would you get here? The people in Watertown were welcoming and accepted Pondexter, burying him as one of their own, yet there persisted a cultural divide that was caused by 100s of years of slavery as illustrated by the word NEGRO on his marker.

ANSWER: 54 or 51 years of age? Research has shown that the tombstone most likely was added many years later. The people who added the stone used an age they believed him to be, explaining the age discrepancy.